|

| Pair of ivory bags with white beads by Lumured, one with a top flap and the other with a zipper. From the collection of The Vintage Purse Museum. |

Special Post: The History of Lumured Handbags

With input from relatives of the company’s founders

Lumured beaded bags have a remarkable and long-lasting history. The massive production output and innovative fabrics are themselves incredible, but the creative geniuses behind the scenes and their decades-long collaboration are what made it an extraordinary company.

Let’s start with something simple—yet very important—that even The Vintage Purse Museum’s curator didn’t know prior to contacting relatives of the company’s founders. Lumured is pronounced “LOO-mer-ed” and is named for its four partners, Louis Madreperl, Ludwig Kaphan, Murray Getter and Ed Kaphan, who started the business in the 1940s. The company was purchased in the 1970s by Lumured employee Adolf Baumgarten, who ran it until the 1990s. Mike Hasko, another employee, was also an owner for a time, as was Frank Kaphan, son of Ed. Per our Q&A with the Kaphans, other sons and a son-in-law of the partners were involved in the business at varying points.

We first became acquainted with the name Ludwig Kaphan when we wrote the story of Plasticflex handbags. Ludwig invented a similar plastic tile fabric as well as the plastic coils that came to be used on what are now known as “telephone” or “phone” cord handbags, which are very desirable among vintage fashion collectors. Ludwig also created and patented the "decorated flexible fabric" that became Lumured handbags.

We had wonderful email discussions with Bob Kaphan and Frank Kaphan, the sons (respectively) of Ludwig Kaphan and Ed Kaphan. This is by far the most detailed account of a company's story and its process of handbag making that we’ve documented on The Vintage Purse Museum’s website. We also spoke with Louis’s grandson Brad Madreperl, who went to the old factory site and snapped some photos. There's a great deal of information, along with photos and old newspaper ads, so be sure to scroll all the way down.

Here is some biographical information about the four men who comprised Lumured, and the man who owned the company in its later years.

Louis Madreperl, 1903-1976, born Louis Madreperla. His Brazilian passport and the 1940 US Census says his birthplace was the US, but his grandson gives his place of birth as Italy.* He retired from Lumured in 1973. According to a 1918 directory, Louis was employed in New Jersey as a glass-cutter at age 15. More info from his grandson below.

Ludwig Kaphan (pronounced CAP-han), 1910-1982, born in Austria. More info from the Kaphan family below.

Murray Getter, 1906-1984, born in New York. A 1933 Brooklyn directory lists him as a salesman.

Ed Kaphan, 1908-2001, born in Austria. More info from the Kaphan family below.

Adolf Baumgarten, (per his obituary) 1932-2020, born in Romania (confirmed in genealogy documents, although the Kaphans remembered him and his two brothers as Ukrainian*), immigrated to the US in 1946, became a machinist, and, after first working at a needle factory, was foreman at the Lumured company, which he would eventually own.

(*The Vintage Purse Museum frequently finds birthplace discrepancies when we research handbag makers. It often has to do with the changing of borders in Europe, mistakes in old documentation or the mystique of family lore. For many Jewish immigrants escaping anti-Semitism, listing different countries of origin was a matter of self-preservation.)

Here’s our (lightly edited) Q&A with Bob Kaphan and Frank Kaphan. It’s written in first-person by Bob, but Bob and Frank collaborated on this well-written, poignant and humorous family history. Memories from Brad Madreperl follow, with fascinating Madreperl family anecdotes.

The Vintage Purse Museum: We found through genealogy records that your father was born in 1910. According to the 1940 US Census, he and your mother Elfrieda “Frieda” Schoenich (1915-2014; they married in 1939) lived in Kings County, New York with your uncle Edward and his wife Elizabeth. At the time your father was a “designer” of “pocketbooks” and Edward worked as a “mechanic” in the “dental instruments” business. They were all born in Austria.

Bob Kaphan: My father and his brother lived in Vienna's First District (Innere Stadt) and left school when they were about 14 years old to help support their family and learn a trade. My grandfather was blind and Ludwig and Ed's older brother, Karl, died at an early age (teens or early 20s) playing handball, probably due to some sort of cardiac abnormality. Ludwig worked his way up in the leather/handbag trade, eventually becoming a Master Leather Craftsman in his early twenties.

He started his own "factory," eventually employing about 20 workers. He sold leather handbags to stores on Mariahilfer Strasse, Vienna's main shopping district. Sometimes the stores would suggest changes which he would honor, since all the products were small lot handmade and could be easily modified for the short production runs.

Ludwig's brother, Ed (Eduard/Edward), also had his own machine shop business making tools and dies for other businesses. They shared a motorcycle with a sidecar that my mother and aunt rode in together, with the two boys on the bike itself.

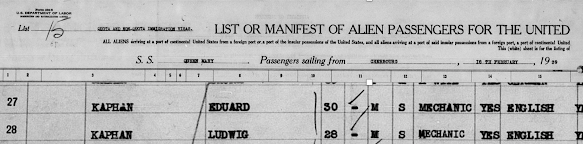

In 1938, when the Nazis confiscated their motorcycle and businesses, Ludwig and Ed were able to obtain visas and move to the US with only a few dollars in their pockets. The crossed on the Queen Mary the last time it carried passengers before becoming a troop ship during WWII.

|

| Screenshots (top and bottom photos combined) of excerpted 1939 Queen Mary passenger list from MyHeritage.com. |

In 1939 their fiances Frieda (Elfrieda) and Elizabeth (Leisl) joined them in the US to be married. It's interesting to note that in those days there was no welfare system of any sort to fall back on. Before being granted a visa, immigrants had to have someone in the US provide the government with written assurances that they would take care of them if they couldn't make it on their own.

|

| Freida, Ludwig, Ed and Liesl at the Latin Quarter in New York. Photo courtesy of the Kaphan family. |

In this country, Ludwig created the materials and designed the styles for three distinct lines of handbags: leather squares held in place by plastic frames; plastic coils laminated onto cotton; beads laminated onto cotton. The coil bags were made by another company, Plastic Fashions, but designed by my father. (UPDATE: MAY 21, 2023: The Vintage Purse Museum's article about plastic coil bags.)

|

| Ludwig Kaphan's coil cord fabric patent, screenshot from Google patents. |

|

| Unusual coil cord handbag, no maker tag, but likely made by Plastic Fashions. From the collection of The Vintage Purse Museum. |

TVPM: Do you know how your father came to be associated with Louis Madreperl? We learned very recently that Lumured was an amalgamation of Louis/Ludwig, Murray and Edward.

BK: Lumured Corporation stock was owned equally by:

Ludwig Kaphan - Handbag Designer, Director

Ed Kaphan - Production Director and designer and builder of all specialized manufacturing machinery

Lou Madreperl – Office Manager, Director and CFO

Murray Getter - Director of Sales

|

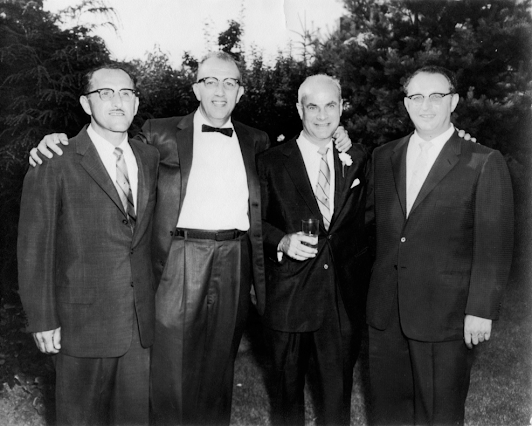

| Lumured partners (left to right), Ed Kaphan, Louis "Lou Perl" Madreperl, Murray Getter, Ludwig Kaphan. Photo courtesy of the Kaphan family. |

Ludwig, Lou, and Murray were employed at a handbag company in New York, as designer, office manager, and salesman. Ed worked for a company making and repairing dental equipment. When Ludwig, Lou and Murray decided to leave and start the handbag business together, my dad said, “We need someone to build the equipment and run the factory. My brother Ed can do that!” And thus was born a partnership that lasted and functioned effectively for 30 years. You can imagine the stress and risks of quitting your job cold turkey to start a new manufacturing business from scratch. These were not risk averse young men.

Frank and I believe my dad was the most important and creative of the four. He was very sharp with numbers as well as developing innovative materials that complemented fashionable and utilitarian designs, but each of the four partners had their own areas of expertise and didn't stick their noses in the others' business unless asked.

|

| Example of the Lumured company imprint on a handbag from the collection of The Vintage Purse Museum. |

Murray Getter, a super salesman, managed the sales office in Manhattan in addition to sales reps around the country. In the early days when the business took off and customers were driving Murray nuts about not getting their deliveries quickly enough, he would go to the factory in Woodbridge, New Jersey on weekends to help pack the orders for shipment. Always looking to maximize sales, he made Lou Perl buy extra-long order books specially printed for the salesmen because he said, “When the salesmen get to the bottom of the page writing style numbers and colors, the customers stop buying.” Longer pages - more sales. He was everyone's best friend, but was actually intense under the surface veneer of affability. He used to call my dad “Ricky” rather than the nickname for Ludwig used by everyone else, “Wicky” (pronounced “Vicky” in German and by everyone in the US), because Murray felt “Vicky” sounded like a girl's name in America.

|

| Per Bob Kaphan, "Everybody's best friend Murray Getter" shown here after being called up onstage at Leon & Eddie's. Photo courtesy of the Kaphan family. |

Louis Madreperl went by the shortened “Lou Perl” in the business world because he thought it sounded more Jewish rather than Italian, as were most manufacturers in the needle trades. Lou was a stickler for detail, which was a plus for running the office of a growing business. When Lou once complained that the books didn't balance perfectly and were off by a few cents and he couldn't figure out why, my happy-go-lucky uncle Eddie took a handful of change out of his pocket and said, “Here, take this and don't worry about it!” Luigi (as my uncle called him sometimes) lost it and said, “I can't do that, I might be off $10,000 on one side and $10,000 and three cents on the other side!” Not likely, but three cents is three cents and the books HAD to balance or Lou couldn't sleep at night. When he left the office, every single item on his list was crossed out, and his desk was bare.

My uncle Eddie was an expert mechanic and tool designer, and was able to get my dad's ideas into volume production using a great variety of creatively designed tools and machinery. He ran the factory with as many as 300 unionized workers at the peak without ever having any labor problems that I'm aware of. He was well liked by all of the employees, as were my dad, Lou and Murray. It was a pretty happy "family" that had huge Christmas parties with wild dancing of the Csardas in a rented hall with a Hungarian band, and bus caravan trips to Atlantic City in the summer. I remember the four partners handing out turkeys as everyone went home before Christmas and walking through the buses handing out envelopes with cash for everyone to spend on the boardwalk in Atlantic City.

|

| Screenshot from the December 23, 1953 Raritan Township and Fords Beacon. |

TVPM: Do you know how many were employed at its peak while your father was a partner the company? (We found a couple of articles about a fire in 1963 and it said 200 employees were evacuated.) Do you remember any standout employees?

BK: When I was employed in the late 1960s there were about 225 employees spread out over three buildings in Woodbridge and Perth Amboy, New Jersey. The national sales office was located in midtown Manhattan on 5th Avenue. Sales reps covered the entire US. For background information, virtually all of the substantial handbag and accessories companies in existence at that time had offices at 347 or 330 Fifth Avenue, across the street from and adjacent to the Empire State Building. Lumured's office was originally at 347, but eventually moved up to the fancier 330 building. The design of our office was modeled after the Bonwit Teller department store on Fifth Avenue with lots of mirrors and tall faux plants.

The fire you referred to wasn't an actual “fire” as you would normally think of it. Part of the process I'll describe later involved 2 side-by-side 30-foot-long ovens with metal mesh conveyor belts and attached dip tanks of highly-flammable acetone. They were protected with baffles that automatically slammed shut in case of fire, and an automatic CO2 fire extinguishing system that had about 8 person-sized CO2 cylinders supplying it. In addition, the entire building where the beading was done had enormous exhaust fans on the roof that turned over the air in the building in less than five minutes. Heating the place was expensive and A/C was out of the question.

When the glass of one of the dozens of heat lamps in those ovens would break and a hot wire filament was exposed to the acetone fumes, it could get pretty exciting as the doors on the oven slammed shut and the many fire extinguishing heads in the oven blasted off. That only happened a couple of times and caused a lot of commotion, but there was never any actual fire in the building, just one big and noisy flash in one of the ovens.

Lumured was a microcosm of the east coast of America in those days. Our employees were mostly immigrants and descendants of recent immigrants of many nationalities, the majority of them of European heritage, especially Hungarian and Polish, as well as a fair amount of Hispanics. The most interesting Lumured employee in the office crew was a “little person” with a big personality. She was so unbelievably fast on an adding machine that you would have to shake your head in disbelief. She would also talk your ear off at the same blinding speed. Before I began working there and computerized the payroll system which included writing checks, a Brinks truck would deliver cash payroll every week. She counted the cash for 225 employees' pay envelopes with blinding speed every week. Lou Perl, of course, had always insisted on double checking the counting of the cash, so we saved a lot of work, and expense, by using checks instead. When I twisted Lou’s arm to allow the use of a check-signing machine for payroll checks (my hand was cramping from signing 225 checks each week), I'm pretty sure Lou slept with the check writing machine under his bed and the key for it on a chain around his neck. Just kidding—he kept it locked up in the office safe. As a sign of the unquestioned trust the partners had in one another, other checks required two partner signatures on them, so my uncle Eddie or sometimes my dad or even Murray, if he was visiting the factory, would go to the office and sign a couple of hundred checks and leave them in the big checkbook for Lou to add his signature when he paid bills.

|

| Lumured bag with interesting rigid handles and white beads on off-white fabric. From the collection of The Vintage Purse Museum. |

You can imagine that with hundreds of employees we had all sorts of characters around. One of the most notable was the man who ran the two plastic extrusion machines all by himself for about 30 years. He wrestled the 300 pound drums of plastic around, shoveled it into the hoppers, ran the chopping machines and punch presses constantly checking sizes and thicknesses of the strands, tubing, and strips we used. He was a Polish Jew with Auschwitz concentration camp numbers tattooed on his arm. You have to believe that after surviving Auschwitz, tossing around barrels of plastic was a piece of cake. He sure knew how to work you over for a raise though, especially since he was running his own one-man fiefdom making all the plastic extrusions and beads for the entire operation. It would have required at least two people to replace him for sure, so he deserved the big bucks.

TVPM: The earliest newspaper ad we could find for Lumured bags was from 1946, and they were leather and reptile. The “beadette” advertisements started around 1947. Do you know how these were constructed? We found Ludwig’s patent for the fabric, but we were wondering about the machines and employees used to make the fabric, frames, hardware, etc. Lumured used the names “caviar,” “beadette,” “grandee” and “corde beads.” We’re especially curious about the “corde,” because that word is generally used to describe a specific type of embroidery made on a Cornely-Bonnaz machine. Do you know anything about its origins?

BK: Ludwig had his first brilliant idea in the US as espoused in the movie “The Graduate": The word to remember for the future is “plastics”! Ludwig attended class in New York at the American Plastics Institute to learn how to use plastics for industrial applications. Lumured's first products were handbags constructed of injection molded plastic squares resembling picture frames with inset exotic skins such as alligator, snake and lizard. The huge idea, aside from adhering the plastic squares to twill fabric by the use of acetone as a solvent saturating the cloth and softening the cellulose acetate plastic instead of messy, slow-drying adhesives (acetone evaporates very quickly; think nail polish remover), was the absolutely crucial idea of buying scrap leather from other handbag companies that had chopped out patterns from the skins for bags totally constructed of alligator or snakeskin, etc. By recycling the scrap skins, the handbags could be sold for a fraction of the price of a bag made from the center of a perfect alligator skin. The leftover small, irregular pieces were large enough so that Lumured workers could chop out small squares with handheld dies and mallets and glue them into the plastic picture frames with a drop of acetone to soften the plastic. Each one had a rotating wheel like a lazy susan with toggle clamps that pressed down on the leather as the acetone dried. Those squares with the alligator inserts were then laid out on a patterned fixture for each style of handbag and fastened to cloth, again by the solvent process using a press, and then the bags were glued and sewn up with linings and various parts just like other handbags.

Around the same time my dad also invented another unique material for “coil” handbags that were manufactured by a company named Plastic Fashions. My father was paid a design fee, and Lumured made the plastic coils for the bags. Ed built a machine that wound thin plastic strands around long metal rods that went through a heater to form the plastic into long coils and then turned the coil in the opposite direction to loosen it and shot the metal rods back into a bin to be pushed back into the winding machine. The coils were laid into patterns for each handbag style, acetone-saturated fabric was laid on top and pressed into the coils, fastening them to the cloth. Then the bags were assembled in the traditional manner, although I believe most of the seams were made with glue because with the ¼” coils hitting each other you couldn't sew a seam without leaving a huge amount of bare cloth around the seam.

Sewing the beaded bags had much the same problem. They were smaller and Ed created all kinds of special sewing machine attachments and one-sided sewing machine feet and “skate” feet to solve the problem. He called them skate feet because they had blades like ice skates that skated between the rows of beads to hold them in place and squeeze them together for sewing the seams on the “left” side as it's known in the industry (inside out). With the large domed beads called “Grandee” beads, which simulated the wooden bead bags that were popular at the time, he created special fixtures to hold the beads and used button sewing machines to stitch around the beads from the “right” side, (the) front side of the bag. The sewing machine operators would close the seams by pressing a pedal to open the fixture, moving the bag to the next bead, close the fixture by lifting their foot, pressing the other pedal to make a button stitch around the beads just like attaching a button to a garment, and so on.

The beaded handbag manufacturing process, which was covered by some of my father’s patents, was a fascinating thing to watch. In spite of having a number of patents, all of the process was a very closely guarded secret for many years.

|

Navy blue Lumured bag with zipper top and architectural pleats. From the collection of The Vintage Purse Museum. |

First plastic powder was dumped into an extrusion machine and made into continuous, solid, square strands. The plastic could be solid, clear or translucent colors. The strands then went through a very noisy chopping machine, which cut the strands into accurately-sized small solid cubes by the millions.

The cubes were attached to the cloth with a solvent process on seven large (ten-foot diameter) round machines with several stations where various operations were performed. The employees we called “beaders” worked at two of the stations. Pieces of cloth that were pre-cut on long cutting tables 150 layers high (everything in the needle trades was done in dozens and grosses (144), so we cut 150 to be sure at least 144 perfect bags came out at the end of production) to individual patterns sized and shaped for every style we made were saturated in acetone and placed on patterns marked on a metal plate that was completely covered with magnets in milled grooves. Drilled or punched metal plates (beads in patterns or placed over embroidered cloth required a set of perfectly matched plates used in stages) with thousands of holes were lowered over the cloth and held down perfectly flat by the magnets in the lower plate. Any looseness would allow two beads to get stuck in one hole—a very big problem. Then the beads were scooped onto the plate and gently rubbed and brushed into the holes. The plates were then tilted up by an air cylinder to dump the excess beads back into a bin and the beader would examine the work to make sure there weren't any missing or double beads to be fixed. Then the machine would move the plates around so a second color, or clear beads over embroidery, could be added by the next beader. The acetone in the cloth softened the beads and when the machine moved to the next station a pneumatic press would push the softened plastic into the cloth, permanently adhering the beads. We received virtually no returns for any defects or loose beads. Pretty amazing, considering the thousands of bags we made each week. The next station on the wheel had a heater to dry the cloth, and at the next station the plates were lifted up and the beaded cloth was removed and examined again for defects. Believe it or not, our largest handbags like the reversibles or three-ways with the smallest, most closely placed beads (Petite bead) had 30,000 (yes, that's 30-thousand) beads on each one. By the way, the tolerances required for the thickness of the screens, spacing of the holes, and sizes of the plastic beads were within a couple thousandths of an inch. The slightest inaccuracy would cause unmanageable problems of missing, loose, or double beads.

The biggest discovery of all was the concept of baking the acetone-saturated tiny cubes of plastic under heating lamps to cause them to blow up and become the round hollow beads you are familiar with on the hundreds of thousands of bags Lumured made.

|

| Lumured reversible drawstring pouch bag, clear and pale pink beads on side pictured, white and clear beads on reverse. From the collection of The Vintage Purse Museum. |

The machinery my uncle Ed created to do that in huge volume consisted of two long ovens with metal mesh conveyor belts running through them. We had two, so that white, and white with crystal beads over embroidery, which was the most popular color for summer-worn beaded bags—far more than all the other colors combined—would be kept separate from other colors that would contaminate the white fabric. At the front of the conveyor, workers would lay the beaded fabric onto the belt and place magnets at the corners to hold it down as the belt traveled down through an acetone bath which would soften the plastic. After the bath, the conveyor continued through the heating oven. As the cubes heated, they would expand into hollow shiny spheres and strongly adhere to the fabric. If the sphere plastic was clear, the resulting beads appeared to sparkle. Depending on the colors, the weather conditions and who knows what else, the time in the bath was controlled by tension on the belt and the level of the acetone in the tank. The temperature of the oven was controlled by powerstats on the heating lamps. We're talking about mysterious dark arts in controlling those factors or the beads didn't blow up the right way, to the right size, or left many square beads un-blown. At the far end of the ovens, the fabric was taken off the belt and the magnets were sent back to the front of the ovens on a narrow canvas conveyor belt to be used again. We even had to buy a magnetizing machine to re-magnetize the magnets as they lost strength over time.

We also made many other parts of our handbags out of plastic that we created in-house. We made curtain rod handles with “facile” hinges, and reversible ones with metal parts we stamped in house, various plastic frames that were hidden inside the top of clutch bags that snapped open and closed, like the one Doris Day carried in the “Glass Bottom Boat” movie.

|

| Doris Day and Dom DeLuise in the 1966 film "The Glass Bottom Boat." Doris Day is carrying a Lumured clutch with snap opening. Photo screenshot from YouTube. |

These handbags were extremely popular for the entire time Lumured was in business. The beaded fabric material now went to departments for traditional “cut and sew,” attaching handles, framing, boxing, warehousing and shipping. We had a box-making machine and made all our own boxes; one employee did nothing but make boxes all day long. By the time the shipping season for spring and summer bags rolled around, the warehouse was jam-packed with thousands and thousands of bags, all produced without knowing which styles would sell the best. Although, after a few years of experience we had a good idea about what to produce ahead of time.

Since Lumured only produced a spring/summer line of handbags, the factory was shut down every year from June through August for retooling for the new styles, and often, new products. Production started in September, the new product line debuted at major sales shows in January, with product shipping early spring through early summer.

The mostly-women unionized labor force was laid off for three months every year, able to collect unemployment compensation. These jobs were coveted because the women had “every summer off” with unemployment benefits, which of course coordinated with school summer vacation. In New Jersey the employer pays unemployment tax based on the company's history, so Lumured was always in the highest paying category.

|

| Lumured clutches similar to the one carried by Doris Day in "The Glass Bottom Boat." The one on the bottom is marked "Petite-Bead." |

Regarding the names of styles, the names Beadette, Corde', etc. have no relation to anything else that I'm aware of, and were just creations of Murray Getter's imagination. I think the sales office just saw the latest material and came up with the names. In the early days, each individual style even had its own name in the sales brochure like the “Missy”, the “Boulevard”, or “What have you that Murray could dream up”. I think “Corde' bead” was used to refer to the bags that had two-tone geometric patterns of beads, and meant nothing else other than perhaps a reference to another popular material of the time. As time went on, the beads got smaller and closer together, hence “Caviar”, but in chronological order (and size order), I think it was Beadette, Corde', Petite. Then came the large domes, Grandee, that were made by an injection molding manufacturer in a mold created and owned by Lumured that had over 500 cavities in it and cost $22,000 to make. That's a pretty penny adjusted for inflation, I would say well over $200,000 today. And a lot more money had to be invested in the tooling for attaching those beads to cloth and constructing the bags in a very different way. Quite risky and done based pretty much on assurances from Murray that he could sell bags like that. Later on, the tile bags were created with ¼” square plastic tiles that were punched out of extruded continuous strips of plastic and sold well. New systems were devised to put a glossy mirror finish on the beads using heated silicone rubber plates in presses with sheets of Mylar.

After the business was sold to Ed's son, Frank, a successful line of evening bags that could be sold in the fall was created using very small flat, punched out, beads that were vapor polished to smooth the edges and then pressed to a high mirror finish in presses. Eventually a method to vacuum plate the plastic “Luma-mesh” was devised that required the purchase of very expensive equipment with a large vacuum deposition chamber.

Ed spoke to Judith Leiber one time. She said she couldn't understand how the hell Lumured could put 10,000 beads on a bag and sell it for $10. At that time, she was already selling her rhinestone “minaudiere” metal boxes for $500 and more. She related the story of how she answered people who said her bags were too tiny to fit anything inside them. Her answer was always, “All you need in your evening bag is a lipstick, a $100 bill and a condom.”

(Note from The Vintage Purse Museum: Many consumers know of high-end handbag maker and Holocaust survivor Judith Leiber, 1921-2018. While it's true that midcentury handbag-manufacturing was a close-knit business and virtually everyone knew everyone, her name has consistently been mentioned to us when we interview relatives and former employees of handbag makers. The above, however, is now our favorite Leiber quote.)

Special machinery was built for lacquering over the plating. Those are the bags you're referring to as metal, which were actually vacuum-plated plastic and a less expensive alternative to Whiting and Davis metal mesh bags. In that time-frame there were a few other new ideas. There were bags made with larger, ½” tiles (Rep-Tile it was named) that were patterned like reptile skins by pressing lace into them with hot silicone rubber plates that were sewn into more conventional faux leather handbag styles, and canvas bags with pictures made out of beads, like zebras and tigers with plastic eyes that were made in-house. There were also multi-color designs made with dyes squirted (“Graffiti”), or brushed (“Melange”) onto the tiles by hand.

I believe the original partners were once offered the metal mesh manufacturing machines from Germany that were eventually used by Whiting and Davis. They passed on them. I guess that's one mistake that they made, but they were never unhappy about the way things turned out.

TVPM: The reversible and three-way Lumured bead bags are always a showstopper for collectors. Do you know anything about these—did your father design them, how many were sold, how they were marketed, etc.?

BK: Ludwig designed them. They were very popular and were just sold alongside all the other styles in our line. There was no direct-to-the-consumer marketing done, and everything was just sold to individual stores and the buyers of the major department store chains from the sales office and by the sales reps around the country. One sales tidbit may be worth relating: One popular reversible handbag had a metal frame. We covered the frame with a matching-colored plastic tube. (Extruded, formed, sliced on the inside on a table router with custom blades and forms, etc, and then snapped over the frame.) A popular TV personality in Puerto Rico had one and showed it on TV and said it was so cool because it reversed, and for several years we sold a quarter million dollars of them annually, and then other styles, on the island of Puerto Rico alone. When Murray went there on a sales trip, the buyers and shop owners from stores on the island were waiting in line in the hallway of the hotel to get into his room to place orders. We figured that every lady in Puerto Rico eventually had one or two of them.

|

| Pair of three-way reversible Lumured bags. The handles come apart so the covers can be changed. From the collection of The Vintage Purse Museum. |

|

| Same bags in photo above, disassembled. |

There was another style, not reversible, but custom made with yellow and green floral embroidery that was made exclusively for the ladies belonging to the charitable organization VISTA, Volunteers in Service to America. They ordered thousands over a few years and, apparently, every lady at their conventions carried their custom Lumured beaded bag all the time. I wish I had a picture.

The most popular reversible of all was the simple little drawstring pouch that you could flip inside out, and people used to throw them into the washing machine when they got dirty with no problems. For years, we had a night shift that basically only made the drawstrings to keep up with the demand. As I recall, at the peak we made 115 gross per week. 16,000+ That's a lot of beads. I don't think the three-way was all that popular. You couldn't do much with the design and it was a little clunky. What I remember was a stiff, ordinary metal-framed bag with a paper box and padded interlining inside to hold its shape and a reversible cover that was held on with metal turnlocks on the bag that went through metal grommets on the cover. That was actually never a big seller compared to the various reversibles. Too bad Velcro hadn't been invented yet.

TVPM: We found a 1976 newspaper notice naming the executors of Louis Madreperl’s estate and it listed your father, uncle, Murray Getter and Roland Winter. (We believe Winter was an attorney for the estate.) Is this around the time the company was sold to Adolf Baumgarten? Did your father and/or Edward retire at this time or did they still work there when Mr. Baumgarten was owner?

BK: Around the mid 1960s Japanese manufacturers started taking advantage of the fact that Lumured’s US patents for the manufacturing process were ending. Early Japanese knockoffs appeared in the US, but were of poor quality and seemed to be no problem for Lumured. However, the quality and designs quickly improved and the imports started to become a competitive threat. Lumured’s new generation (Frank, Lou Perl's son Warren, Murray Getter's son-in-law Jerry Gelbwaks and I) believed the company needed to diversify to remain competitive. Frank and I were anxious to put our newly minted engineering degrees and MBAs to work. Our fathers took a slower approach.

Around 1970, as sales continued slipping, the handwriting was on the wall. Frank, Warren, Jerry and I, not being able to convince the partners to shift business gears, all left Lumured to pursue other careers. When the partners realized that all the young blood was gone, they decided to actually retire. In 1974, Frank's dad convinced him to come back and take over the business by just buying the real estate and agreeing to use up all the inventory of handbags and materials and pay them off at a discounted price over several years. All of the machinery and equipment was thrown into the deal for free. Adolf Baumgarten and Mike Hasko who had been longtime employees of Lumured were included as minority shareholders and continued to operate the business with him and about 100 employees during busy times. None of the original partners were involved in the business after 1974. Mike Hasko retired in 1983 and his share of the business was bought by Frank and Adolf. In 1987, Frank finally sold his interest to Adolf, essentially the same way they had bought the business from the original partners, and Adolf operated the business for many years with his son David, who had already been working there for several years.

By the time Adolf owned the business, the handbag side of it was largely decimated by cheap imported copies manufactured in Asia. Most of his operation consisted of making the various beaded fabrics which were sold to manufacturers for use in other products, or packaged to be sold in craft stores for home sewers and crafters as iron-ons, etc. One interesting note is that I heard some, I don't know how much, of our mesh material made it into Hollywood movie costumes as part of sci-fi characters' futuristic costumes/uniforms, etc.

Adolf originally was a machinist who learned his skills in Germany, and told the story (repeatedly) of the teacher who made the students create a perfect steel cube using only a file. The teacher said, “What are you going to do if you're in the middle of the jungle in Uruguay and only have hand tools?” He was working in the machine shop that did some work for Lumured, and Eddie stole him away to run the machine shop in the Lumured factory. Over time he turned out to be extremely versatile and became a jack of all trades at Lumured, eventually running the entire plastics/beading department which was in a building of its own. Ed taught him all about repairing the 100+ sewing machines, and of course he worked on all the machinery and fixtures throughout the business. Uncle Ed, more than any of the other partners found ways to develop people and then give away his responsibilities to others.

Ludwig Kaphan passed from a heart attack on a trip to Austria while hiking in his beloved Austrian Alps. It was a great shock to everyone back in the US, but I suppose from his perspective it was a pretty good way to go. His beloved wife, my mom Frieda, lived to the age of 98 in the snowy state of Vermont, still downhill skiing to the age of 88.

***

Here’s what Brad Madreperl, grandson of Louis, had to share with us (lightly edited). Brad recently went to the company’s former location and took photos of the building.

“So I took a short trip down memory lane this past week and visited the old buildings at 292 E. Smith St. in Woodbridge, New Jersey, where Lumured manufactured their successful era of beaded purses. Amazingly the buildings remain standing right in the midst of its original old European neighborhood. I would say the four partners kicked off their pocketbook-manufacturing business (in) 1946-1947, around the time their 25-year patent was approved for making ‘beaded pocketbooks.’

|

| Former location of the Lumured factory in Woodbridge, New Jersey. Photo courtesy of Brad Madreperl. |

Always remember that the 25-year patent ran out 1971-1972, and from there on Japanese manufacturers started to take over the market for producing those purses with their cheaper production costs and pricing. From there my grandfather retired in '73, attended my first marriage in July, '74 and passed away exactly two years later. He spent those last two years of (his) life mainly racing the (two or three) trotter horses he owned at Freehold (harness horse) Raceway, NJ. My grandfather and his sister came to America from Northern Italy through Ellis Island. He chose to remove the ‘a’ off the end of our family name so he could (I heard) more subtly pass as another Jewish partner. Madreperla actually means 'Mother of Pearl' in Italian.

|

| Louis Madreperl's Brazilian passport, screenshot from MyHeritage.com. |

I know they had a showroom in NYC, 5th Avenue, but I don't recall ever seeing that. In his Woodbridge office there was a photo of my grandfather with Jayne Mansfield posed in Miami with a Lumured purse that was seen in a movie in which she was featured. That had to be a true highlight for his business career! My father Warren managed the sewing room where the already beaded materials were put together with the metal hardware frames and attachments. There were rows of local women of European descent, each sitting in front of a sewing machine. Polish, Hungarian, German, Russian, Portuguese, etc. ALL with thick accents. It was a melting pot of workers and my dad seemed to work well with them and in turn it appeared he was respected by all. I think it was a happy place for people of differing cultures to have worked. When my sister and I visited, many of them fussed over us. They were a happy bunch.

One day, in the early 1950s, there was a tragic train derailment that occurred at the end of Lumured's street. The next day there was a front-page photo on one of the big New York newspapers and it showed my dad pulling passengers out of the side windows which were facing upward. He was a former Merchant Marine.

The main factory, facing E. Smith St., was where men and some women worked the patented beading process. I recall they started with black or white cloth materials, cut to pattern dimensions, then laid out on a meshed metal conveyor belt that were then secured to the belt by 2-inch magnet bars. Then a frame with patterned holes was placed over the material and tiny plastic cubes (black or whites) were sifted onto the material leaving the designed pattern of beads on the frame. I believe acetone was used at some time during this process. Then the machinery is turned on and the metallic mesh conveyor belt runs under high heated lamps. When the pieces come out the other end the small plastic cubes have melted into small, spherical beads that are now melted onto the pocketbook material. By the 1960s I believe the Lumured purses evolved into white material with a pink flower design which was then covered with clear plastic beads made with the same patented method.”

***

The Vintage Purse Museum briefly corresponded with a relative of Adolf Baumgarten who offered this explanation for the metal-like tiles that were created during Baumgarten’s ownership: “By the 70s, they were losing ground to the metallics of the likes of Whiting & Davis, and of course, plastics didn’t have the caché of the metallics.”

***

When we asked the Kaphan cousins if there was anything else they wanted to share, they told us that Lou and Murray were part of a great team and an excellent front office manager and great salesman and manager of the sales reps. Ludwig and Eddie, they said, were the heart and soul of the innovative and mass-produced affordable beaded bag that virtually any woman could afford and feel stylish carrying.

***

The Vintage Purse Museum is extremely grateful to Bob Kaphan, Frank Kaphan and Brad Madreperl for their outstanding contributions to this post. Other information was found in the newspaper archive Newspapers.com and the genealogy website Myheritage.com, to which we have paid subscriptions. This article c2022 Wendy Dager/The Vintage Purse Museum. Please do not reprint any portion of this article or photos without permission of The Vintage Purse Museum, vintagepursemuseum@gmail.com.

Comments

Post a Comment